ARTIST PROFILE

Pastel Master Irving Petlin

By Gwyn McAllister

Artist Irving Petlin has led a remarkable life. He has enjoyed great success and mingled with groundbreakers and luminaries in two worlds – both in his creative pursuits and in his human rights efforts. He’s earned a reputation both for his art and for his role as one of the most recognized artist/activists who led the fight against U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. And both his political and artistic pursuits have been of equal importance to him.

In his long career as an artist Mr. Petlin has been acquainted with some of the world’s most successful contemporary artists, as well as a number of the legendary beat poets and writers. His work has hung in the renowned museums of the world, and he has spent time variously in Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York and Paris – where he lives today – splitting his time between an apartment in the 5th Arrondisment and an 18th century farm in Chilmark.

Running concurrently with his career as a painter and pastel artist, has been a lifelong commitment to political – in particular anti-war – initiatives. During the Vietnam War era Mr. Petlin was an organizer of both the Los Angeles Artist Protest Committee and the Art Workers Coalition in New York City. “I literally gave ten years of my life trying to end the war,” says Mr. Petlin, a strikingly handsome man, whose vitality and impressive mane of thick curly white hair bely his almost 80 years.

Though he has spent summers living and working on the Vineyard for 38 years, the artist had never had a public showing of his work on Island – until this year. The A Gallery in Oak Bluffs has the distinction of being the first Vineyard venue to host an exhibition of Mr. Petlin’s dreamlike allegorical work.

“For years people asked me, ‘Why don’t you have a show here?’” said the artist in an interview at his Chilmark studio, “The artists on the Vineyard only have a short window to show their work. Why should I take up that window when I sell elsewhere?”

Elsewhere being prestigious galleries all over Europe and many of the major American cities including New York, San Francisco, Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia and Los Angeles. Petlin’s work is included in the permanent collections of New York City’s Metropolitan Museum, Whitney Museum, Museum of Modern Art and the Jewish Museum, the Pompidou Center in Paris, London’s Barbican Centre, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington D.C., The Los Angeles County Museum, The Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of Art and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts – to name a few.

Mr. Petlin is known as one of the modern masters of pastel – a medium that he focuses on exclusively while at his summer home on the Vineyard.

“I started working in pastels while I was in Arles in 1961,” said Mr. Petlin, “It was hot. I was working on a balcony with the city and the dust. When I came to the Vineyard in ‘76 it turned out that the pastels were transportable. I associate it with the summer – the dust, the heat.”

Oftentimes, subject matter that Mr. Petlin has explores in pastels while at his home in Chilmark winds up as the theme for oil paintings that he creates at his studio in Paris. “The pastel or the idea of drawing is a way of scouting subject mater for the paintings,” he says. “You kind of explore things with pastels. It acts as a scout for your mind. You experiment with material you haven’t tried out before. Some people call it dry painting. To me it’s more beautiful than a painting in many ways.”

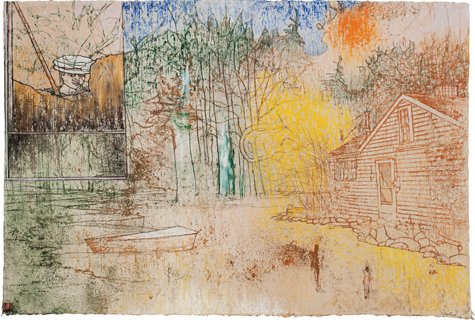

Through stark contrasts of color and varying textures, created in part by using the finest of handmade papers and a medium that lends itself to both fine line and atmospheric color, Mr Petlin creates works that are both visually striking and compellingly complex. They can be appreciated on dual levels – the aesthetic as well as the intellectual.

Mr. Petlin works in the lower level of an historic barn which was once used as a stable by the actor Jimmy Cagney. The studio is reached by ascending a narrow path behind the barn turned house, which is the summer home that he shares with his wife, poet Sarah Petlin. “I loved working here from the very beginning,” he says of the Vineyard, “I found that I was very productive here.”

Mr. Petlin proudly explains that the farm where he lives and works is the 13th oldest in Chilmark – having been constructed in 1719. The property includes four buildings – the farmhouse that was once an inn frequented by visitors traversing the length of the Island, the barn where the Petlins now reside, a windmill/pump house, and the creamery, a small cottage that was the couple’s first Vineyard home.

While Mr. Petlin and his wife enjoy an idyllic existence today, the artist has thrown himself into the fray for most of his adult life – getting involved in the American Civil rights movement, anti-war protests during both the Vietnam and Gulf Wars and other conflicts in both the U. S. And Europe.

From military man to anti-war leader Mr. Petlin, who is the son of Russian Jewish immigrants from Chicago, studied at both the University of Chicago and the Art Institute of Chicago during the height of the Chicago Imagist Movement. Among his classmates were sculptor Claes Oldenberg (a close friend) and pop artist Robert Indiana.

In 1956 Mr. Petlin obtained a full scholarship to Yale University, having been recruited by famed artist and art educator Joseph Albers. Mr. Petlin earned a masters degree in painting before he was drafted into the army.

It was while serving two years in San Francisco in military intelligence that Mr. Petlin became immersed in the world of the beats. “At night I met all of these people – Ginsberg, Corso, McClure. All of them,” he says. He also found time to paint – renting a studio in San Francisco’s famed Bohemian center, the Monkey Block.

After completing his military service Petlin travelled to Paris on a Ryerson fellowship. En route he met his wife Sarah, to whom he is still happily married today.

In Paris Mr. Petlin started to enjoy critical and popular success as an artist. He showed his work in the same gallery as some of the prominent surrealists of the day included Max Ernst and Roberto Matta. He met Giacometti and Balthus, among others.

“Europe was going through a recovery,” he says, “It’s not what it is now. Everybody was poor, but everybody was doing stuff - painting, working raising families. You didn’t have to have a lot of money to survive.”

As much as he loved the Paris scene and his life there as a family man, Mr. Petlin was drawn back to the home of his birth by a sense of duty.

“I was in France during the time of the Algerian War of Independence. I saw what can happen to a country in that kind of a struggle. The American Civil Rights movement had just started and I sensed the beginnings of the Vietnam War. I said to Sarah, ‘I can’t stay here while all of this is going on. A chapter of American life is beginning and we need to be part of it.’”

In 1963 The couple moved to Los Angeles. Mr. Petlin served as a visiting professor at UCLA. The time was a precarious one is the U.S. with the conflict in Asia on the verge of dividing the nation. “It was the beginning of the artist movement against the war in Vietnam,” says Mr. Petlin.

Mr. Petlin was among the most actively involved of American artists working towards peace. As one of the founders of the Los Angeles based Artists Protest Committee, he organized the erection of the Peace Tower, a 58 foot steel tetrahedron by sculptor Mark Di Suvero which displayed over 400 paintings donated by artists including Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, and Frank Stella . Among those who were drawn to rallies at the Peace Tower were Susan Sontag, Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters.

Mr. Petlin recalls defending the tower against vandals during the four months that it stood as s symbol of protest. He famously warded off one would be attacker with a broken lightbulb.

In 1966 the Petlins moved to New York City where Mr. Petlin spent worked as a professor at Cooper Union. He continued his involvement in the peace movement, playing an important role in the Art Workers Coalition’s (AWC) opposition efforts. The AWC was a organization comprised of artists, art critics and dealers that took on many of the major art institutions in New York City on a variety of civil rights issues.

Among those involved in the AWC were some household names. “I knew [Robert] Rauschenberg, [Jasper] Johns, Frank Stella,” says Mr. Petlin, “There was very little distinction between artists who were well known and making money and young artists who were just starting out. It was a time when people were able to submerge their own egos for an effort.”

Many of the Coalition members remained active, even after the group disbanded in 1971. “We kept up all the way up to the Iraq War years,” says Mr. Petlin, “hosting various events around the Attica Riots and the U.S. Intervention in Central America.”

Bi-Continental Life: Paris and the Vineyard

Around the time of the Gulf War, Mr. Petlin finally became disillusioned with U.S. policy and decided to return to Paris, after 28 years in New York. “I needed desperately to devote myself more to my work,” he says, “I needed also to redeem the promise I had made to Sarah to return to Paris. .”

By this time, Mr. Petlin had become very well respected in the international art world. His work was being sold in galleries throughout Europe and the U.S. He had been among the artists included in the Paris Biennal (1961), the Whitney [Museum of Art, NYC] Biennial (1973) and the Venice Bienale (1982).

Although early on in his career he was influenced by the surrealists and abstract expressionists, Mr. Petlin eventually forged his own style, using, variously, pastels and oils, to depict dreamlike landscapes featuring allegorical figures.

He sometimes employs diptychs or triptychs to tell a complex story, generally one with a political or a humanist message. The pastel drawings and paintings are often dissected giving a kaleidoscope effect, or feature figures separated from the scene by a small frame, or hovering ghostlike over the landscape. All of the elements have symbolism – from the sketchy city skylines or massive mountainous backdrops, to the often faceless, sometimes indistinct or only partially realized figures. Some symbols are repeated like the image of “the stopped watch” featured in a series of pastels from a recent Paris exhibit. The watch represents the timepiece found in the rubble after the bombing of Hiroshima.

The artist’s palette covers a wide range. He uses contrast – vivid blues, yellows and reds punctuating stark sepia and earth toned landscapes. Mr. Petlin purchases all of his pastels from the Maison de Pastel de Henri Roche, who have been hand making pastels in France for years and were the suppliers for Degas, Redon and other artists of note. Mr. Petlin explains that the sticks are pure pigment from nature hand rolled today by two women who jealously guard the secret to their purity and brilliance.

At his studio in Chilmark, boxes of these pastels draw one’s attention. They are remarkable for their striking color and - whittled down by use into a variety of shapes and sizes, and sorted into color groupings in wooden boxes - they present a form of artwork on their own.

Mr. Petlin uses his time on the Vineyard to create work that he will then show in Paris during the fall and winter. However, this year, in a reversal of tradition, he worked on the Vineyard paintings all spring in Paris so that he would have a body of work ready for the A Gallery show in August. Appropriately then, given the distance from his subject, the theme of show draws on the quality of recollection and imaginings.

The show was titled Mythology … and the Island. “All Islands have mythology of some kind,” says Mr. Petlin, “Going back to the Greeks. For me the mythology of the Vineyard has to do with absences. When you’re away from it and you think about it, it takes on almost a symbology in your mind.” Referring to the show’s theme, he says, “It’s a personal mythology as well as a general mythology.”

The personal is very much the focus of one of the trio of series in the show. “The Cottage” drawings feature the Creamery – the same Chilmark structure that was the very first home that Mr. Petlin owned, and that represents his fond memories of his past life with his family on the Island. The Petlins, along with two other families, scraped together enough money to collectively purchase the property in 1976. The cottage, where Petlin, his wife and two children, spent many a summer, holds fond memories continuing on through the present day when children and grandchildren now come to visit.

The second series “The Fish and the Boat” are representative of the very essence of the Vineyard itself. “The Three Brothers” series envisions a scene where Mr. Petlin and his siblings are united on the beach, something that has only occurred in the artist’s imagination.

Symbols and Myths

Mythology has always played a part in the artist’s work. As has the idea of the elusive and shifting nature of memory. He has a tendency to draw on Greek myths, Biblical stories, Shakespeare and a host of other sources to comment on current situations or universal themes.

There are a number of recurring figures which pop up in Mr. Petlin’s work - whether he’s depicting a Paris scene, a wooded landscape or a beach. Among them are “The Guardian of Memory” – who, staff in hand, has the look of a character from classical antiquity. Images of wanderers are also commonly found in the artist’s work. They are often depicted traveling on foot or by boat – another of Mr. Petlin’s favored symbols. “It’s the nature of our lives - whether we actually live it or not - to be interested in what’s over there,” says Mr. Petlin, “It’s a kind of yearning for knowledge beyond the horizon.”

The artist’s work has a dreamlike quality with figures overshadowed by the landscape but, still, very much the focal point. There is something somewhat foreboding about Mr. Petlin’s images, a sense of unrest, a seeking. His landscapes have an almost apocalyptic feel. There is clearly a sense of both a universal and a personal voyage – one whose realization is, as yet, undetermined.

Mr. Petlin’s own remarkable odyssey – his struggles, his victories and his frustrations - have certainly informed his work. Still, the overarching message is one of optimism.

“I transform ordinariness into something wondrous as a matter of course,” says the artist, “The ordinary world we live in, despite its falseness and despite its toxic nature, is capable of being transformed meteorically. It’s important to show people that they can take things and alter them. I did it artistically and I did it politically.”

A characteristic understatement from a man whose selflessness is matched only by his gentle humility.

In his long career as an artist Mr. Petlin has been acquainted with some of the world’s most successful contemporary artists, as well as a number of the legendary beat poets and writers. His work has hung in the renowned museums of the world, and he has spent time variously in Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York and Paris – where he lives today – splitting his time between an apartment in the 5th Arrondisment and an 18th century farm in Chilmark.

Running concurrently with his career as a painter and pastel artist, has been a lifelong commitment to political – in particular anti-war – initiatives. During the Vietnam War era Mr. Petlin was an organizer of both the Los Angeles Artist Protest Committee and the Art Workers Coalition in New York City. “I literally gave ten years of my life trying to end the war,” says Mr. Petlin, a strikingly handsome man, whose vitality and impressive mane of thick curly white hair bely his almost 80 years.

Though he has spent summers living and working on the Vineyard for 38 years, the artist had never had a public showing of his work on Island – until this year. The A Gallery in Oak Bluffs has the distinction of being the first Vineyard venue to host an exhibition of Mr. Petlin’s dreamlike allegorical work.

“For years people asked me, ‘Why don’t you have a show here?’” said the artist in an interview at his Chilmark studio, “The artists on the Vineyard only have a short window to show their work. Why should I take up that window when I sell elsewhere?”

Elsewhere being prestigious galleries all over Europe and many of the major American cities including New York, San Francisco, Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia and Los Angeles. Petlin’s work is included in the permanent collections of New York City’s Metropolitan Museum, Whitney Museum, Museum of Modern Art and the Jewish Museum, the Pompidou Center in Paris, London’s Barbican Centre, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington D.C., The Los Angeles County Museum, The Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of Art and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts – to name a few.

Mr. Petlin is known as one of the modern masters of pastel – a medium that he focuses on exclusively while at his summer home on the Vineyard.

“I started working in pastels while I was in Arles in 1961,” said Mr. Petlin, “It was hot. I was working on a balcony with the city and the dust. When I came to the Vineyard in ‘76 it turned out that the pastels were transportable. I associate it with the summer – the dust, the heat.”

Oftentimes, subject matter that Mr. Petlin has explores in pastels while at his home in Chilmark winds up as the theme for oil paintings that he creates at his studio in Paris. “The pastel or the idea of drawing is a way of scouting subject mater for the paintings,” he says. “You kind of explore things with pastels. It acts as a scout for your mind. You experiment with material you haven’t tried out before. Some people call it dry painting. To me it’s more beautiful than a painting in many ways.”

Through stark contrasts of color and varying textures, created in part by using the finest of handmade papers and a medium that lends itself to both fine line and atmospheric color, Mr Petlin creates works that are both visually striking and compellingly complex. They can be appreciated on dual levels – the aesthetic as well as the intellectual.

Mr. Petlin works in the lower level of an historic barn which was once used as a stable by the actor Jimmy Cagney. The studio is reached by ascending a narrow path behind the barn turned house, which is the summer home that he shares with his wife, poet Sarah Petlin. “I loved working here from the very beginning,” he says of the Vineyard, “I found that I was very productive here.”

Mr. Petlin proudly explains that the farm where he lives and works is the 13th oldest in Chilmark – having been constructed in 1719. The property includes four buildings – the farmhouse that was once an inn frequented by visitors traversing the length of the Island, the barn where the Petlins now reside, a windmill/pump house, and the creamery, a small cottage that was the couple’s first Vineyard home.

While Mr. Petlin and his wife enjoy an idyllic existence today, the artist has thrown himself into the fray for most of his adult life – getting involved in the American Civil rights movement, anti-war protests during both the Vietnam and Gulf Wars and other conflicts in both the U. S. And Europe.

From military man to anti-war leader Mr. Petlin, who is the son of Russian Jewish immigrants from Chicago, studied at both the University of Chicago and the Art Institute of Chicago during the height of the Chicago Imagist Movement. Among his classmates were sculptor Claes Oldenberg (a close friend) and pop artist Robert Indiana.

In 1956 Mr. Petlin obtained a full scholarship to Yale University, having been recruited by famed artist and art educator Joseph Albers. Mr. Petlin earned a masters degree in painting before he was drafted into the army.

It was while serving two years in San Francisco in military intelligence that Mr. Petlin became immersed in the world of the beats. “At night I met all of these people – Ginsberg, Corso, McClure. All of them,” he says. He also found time to paint – renting a studio in San Francisco’s famed Bohemian center, the Monkey Block.

After completing his military service Petlin travelled to Paris on a Ryerson fellowship. En route he met his wife Sarah, to whom he is still happily married today.

In Paris Mr. Petlin started to enjoy critical and popular success as an artist. He showed his work in the same gallery as some of the prominent surrealists of the day included Max Ernst and Roberto Matta. He met Giacometti and Balthus, among others.

“Europe was going through a recovery,” he says, “It’s not what it is now. Everybody was poor, but everybody was doing stuff - painting, working raising families. You didn’t have to have a lot of money to survive.”

As much as he loved the Paris scene and his life there as a family man, Mr. Petlin was drawn back to the home of his birth by a sense of duty.

“I was in France during the time of the Algerian War of Independence. I saw what can happen to a country in that kind of a struggle. The American Civil Rights movement had just started and I sensed the beginnings of the Vietnam War. I said to Sarah, ‘I can’t stay here while all of this is going on. A chapter of American life is beginning and we need to be part of it.’”

In 1963 The couple moved to Los Angeles. Mr. Petlin served as a visiting professor at UCLA. The time was a precarious one is the U.S. with the conflict in Asia on the verge of dividing the nation. “It was the beginning of the artist movement against the war in Vietnam,” says Mr. Petlin.

Mr. Petlin was among the most actively involved of American artists working towards peace. As one of the founders of the Los Angeles based Artists Protest Committee, he organized the erection of the Peace Tower, a 58 foot steel tetrahedron by sculptor Mark Di Suvero which displayed over 400 paintings donated by artists including Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, and Frank Stella . Among those who were drawn to rallies at the Peace Tower were Susan Sontag, Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters.

Mr. Petlin recalls defending the tower against vandals during the four months that it stood as s symbol of protest. He famously warded off one would be attacker with a broken lightbulb.

In 1966 the Petlins moved to New York City where Mr. Petlin spent worked as a professor at Cooper Union. He continued his involvement in the peace movement, playing an important role in the Art Workers Coalition’s (AWC) opposition efforts. The AWC was a organization comprised of artists, art critics and dealers that took on many of the major art institutions in New York City on a variety of civil rights issues.

Among those involved in the AWC were some household names. “I knew [Robert] Rauschenberg, [Jasper] Johns, Frank Stella,” says Mr. Petlin, “There was very little distinction between artists who were well known and making money and young artists who were just starting out. It was a time when people were able to submerge their own egos for an effort.”

Many of the Coalition members remained active, even after the group disbanded in 1971. “We kept up all the way up to the Iraq War years,” says Mr. Petlin, “hosting various events around the Attica Riots and the U.S. Intervention in Central America.”

Bi-Continental Life: Paris and the Vineyard

Around the time of the Gulf War, Mr. Petlin finally became disillusioned with U.S. policy and decided to return to Paris, after 28 years in New York. “I needed desperately to devote myself more to my work,” he says, “I needed also to redeem the promise I had made to Sarah to return to Paris. .”

By this time, Mr. Petlin had become very well respected in the international art world. His work was being sold in galleries throughout Europe and the U.S. He had been among the artists included in the Paris Biennal (1961), the Whitney [Museum of Art, NYC] Biennial (1973) and the Venice Bienale (1982).

Although early on in his career he was influenced by the surrealists and abstract expressionists, Mr. Petlin eventually forged his own style, using, variously, pastels and oils, to depict dreamlike landscapes featuring allegorical figures.

He sometimes employs diptychs or triptychs to tell a complex story, generally one with a political or a humanist message. The pastel drawings and paintings are often dissected giving a kaleidoscope effect, or feature figures separated from the scene by a small frame, or hovering ghostlike over the landscape. All of the elements have symbolism – from the sketchy city skylines or massive mountainous backdrops, to the often faceless, sometimes indistinct or only partially realized figures. Some symbols are repeated like the image of “the stopped watch” featured in a series of pastels from a recent Paris exhibit. The watch represents the timepiece found in the rubble after the bombing of Hiroshima.

The artist’s palette covers a wide range. He uses contrast – vivid blues, yellows and reds punctuating stark sepia and earth toned landscapes. Mr. Petlin purchases all of his pastels from the Maison de Pastel de Henri Roche, who have been hand making pastels in France for years and were the suppliers for Degas, Redon and other artists of note. Mr. Petlin explains that the sticks are pure pigment from nature hand rolled today by two women who jealously guard the secret to their purity and brilliance.

At his studio in Chilmark, boxes of these pastels draw one’s attention. They are remarkable for their striking color and - whittled down by use into a variety of shapes and sizes, and sorted into color groupings in wooden boxes - they present a form of artwork on their own.

Mr. Petlin uses his time on the Vineyard to create work that he will then show in Paris during the fall and winter. However, this year, in a reversal of tradition, he worked on the Vineyard paintings all spring in Paris so that he would have a body of work ready for the A Gallery show in August. Appropriately then, given the distance from his subject, the theme of show draws on the quality of recollection and imaginings.

The show was titled Mythology … and the Island. “All Islands have mythology of some kind,” says Mr. Petlin, “Going back to the Greeks. For me the mythology of the Vineyard has to do with absences. When you’re away from it and you think about it, it takes on almost a symbology in your mind.” Referring to the show’s theme, he says, “It’s a personal mythology as well as a general mythology.”

The personal is very much the focus of one of the trio of series in the show. “The Cottage” drawings feature the Creamery – the same Chilmark structure that was the very first home that Mr. Petlin owned, and that represents his fond memories of his past life with his family on the Island. The Petlins, along with two other families, scraped together enough money to collectively purchase the property in 1976. The cottage, where Petlin, his wife and two children, spent many a summer, holds fond memories continuing on through the present day when children and grandchildren now come to visit.

The second series “The Fish and the Boat” are representative of the very essence of the Vineyard itself. “The Three Brothers” series envisions a scene where Mr. Petlin and his siblings are united on the beach, something that has only occurred in the artist’s imagination.

Symbols and Myths

Mythology has always played a part in the artist’s work. As has the idea of the elusive and shifting nature of memory. He has a tendency to draw on Greek myths, Biblical stories, Shakespeare and a host of other sources to comment on current situations or universal themes.

There are a number of recurring figures which pop up in Mr. Petlin’s work - whether he’s depicting a Paris scene, a wooded landscape or a beach. Among them are “The Guardian of Memory” – who, staff in hand, has the look of a character from classical antiquity. Images of wanderers are also commonly found in the artist’s work. They are often depicted traveling on foot or by boat – another of Mr. Petlin’s favored symbols. “It’s the nature of our lives - whether we actually live it or not - to be interested in what’s over there,” says Mr. Petlin, “It’s a kind of yearning for knowledge beyond the horizon.”

The artist’s work has a dreamlike quality with figures overshadowed by the landscape but, still, very much the focal point. There is something somewhat foreboding about Mr. Petlin’s images, a sense of unrest, a seeking. His landscapes have an almost apocalyptic feel. There is clearly a sense of both a universal and a personal voyage – one whose realization is, as yet, undetermined.

Mr. Petlin’s own remarkable odyssey – his struggles, his victories and his frustrations - have certainly informed his work. Still, the overarching message is one of optimism.

“I transform ordinariness into something wondrous as a matter of course,” says the artist, “The ordinary world we live in, despite its falseness and despite its toxic nature, is capable of being transformed meteorically. It’s important to show people that they can take things and alter them. I did it artistically and I did it politically.”

A characteristic understatement from a man whose selflessness is matched only by his gentle humility.