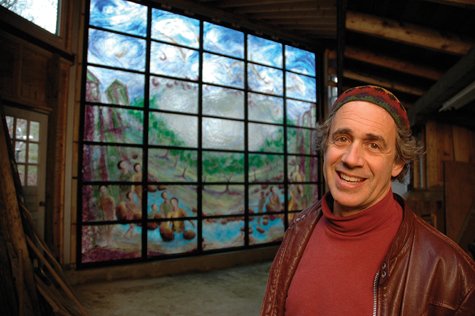

ARTIST PROFILE

Barney Zeitz

Four Decades Forging Glass and Steel

Profile by Nis Kildegaard

Barney Zeitz came to Martha’s Vineyard in the spring of 1972, at the age of 21, on a semester off from the University of Massachusetts that has lasted,

so far, for 40 years.

Growing up in Fall River, where his father worked selling corrugated boxes and packaging, the Island was a familiar weekend haunt for Barney. He recalls hanging out with a friend who had a place in Oak Bluffs, loving the diversity of the integrated summer community.

Barney hadn’t studied art in college – he was enrolled in an experimental program at the Amherst campus, with smaller classes and its own curriculum. “We read existential novels, and we had a whole course on revolution,” he recalls. That class must have been inspiring, because he became involved in the student antiwar activism of the day, at one point shutting down the campus.

Thinking back on those college years, Barney says: “I was pretty stressed out – it wasn’t an easy time for me. I mean, I was just a kid.”

Onthe Vineyard that spring 40 years ago, Barney recalls, “I picked up a book on how to do stained glass at a crafts store, and I bought $50 worth of stuff and made my first little lamp.” It was a kerosene lamp with a stained-glass shade; he set it on David Crohan’s piano at the Rare Duck Lounge on Circuit Avenue, and in one of those messages from the universe that shapes the course of a lifetime, the lamp sold the first night. What’s more, another couple at the table with the buyers commissioned Barney to make a stained-glass chandelier for them.

His career was launched. “I thought, I’m just going to keep going with this until I can’t do it anymore.”

Barney lived for two years in the back of the old Arts Collaborative building on Union Street in Vineyard Haven, just up from the ferry landing. “I had a little workbench in the front, and I made mirrors and boxes.” It was during these years that he learned to make his art windows, stained glass pieces whose leading served as the lines in the art. He refers to that process now as “pushing the lines around.”

When the Arts Collaborative closed, Barney rented a place from Mollie Kahn, whose Vineyard Arts shop was located in what is now the arts district of Oak Bluffs. As he recalls it, this was a time of intense learning and experimentation. It was also the time when he learned to weld, becoming the worker in metal and glass that he is today.

“I lived there for 12 years,” Barney says, “and I made windows that were so tall they wouldn’t even stand up in the room. I eventually outgrew the space, but my landlady, Mollie Kahn, was just a fabulous person. She loved what I was trying to do, this quest to make art that had some meaning to it. She was all about that.”

Mrs. Kahn had made money in the pottery supply business with her husband, who had died a few years earlier. Her place was filled with pottery materials, welding equipment and a kiln, a perfect laboratory for the young artist. “A lot of the chemicals I work with now,” Barney says, “were meant to be glazes for pottery. I’d take them and comb them onto glass, and I’d use Mollie’s kiln, doing these experiments. That was such a great opportunity – it was almost like being in art school, except I had to teach myself.”

Growing up as a self-taught artist, without a mentor, is an experience that cuts both ways, Barney reflects now. “I was an outsider right from day one,” he says with a wry grin. “I’m such an outsider, I don’t even get invited to the outsider art shows.”

But without a teacher to tell him what’s impossible, Barney was free to succeed by failing repeatedly, with enthusiasm. “I find that not having a teacher, I never copied my teacher’s style. I ended up doing things my way.”

Geology, the science of rocks, has been described as the study of heat, pressure and time. These same three ingredients inform the art of Barney Zeitz so fully that each completed work feels at once both effortless and the product of an intensely physical creative process. None of his work is conventionally pretty: Instead there’s an elemental beauty that celebrates both the recalcitrance of glass and steel, and the hard labor of the artist who burns and smelts and cuts and pounds them to his will.

Barney cheerfully describes the work of creating his art as “dirty, nasty, smelly, disgusting.” He’s a regular at the Vineyard Haven office of optometrist George Santos, having fragments of metal dug out of his eyes. He wears goggles, but sometimes the effort of his work dislodges the respirator just enough so a sliver of steel can ricochet in.

“The welding,” says Barney, “is very physically challenging, but I still like doing it. I don’t know how much longer I’ll be doing it, but I’ll definitely keep welding until I can’t do it anymore.”

Barney began welding during his years renting from Mollie Kahn, at first because he wanted to build his own frames. “I learned at the regional high school: adult ed, six Monday nights with a guy named John Holmes, in 1979.”

Now, he says, “Nobody else welds stainless steel the way I do. Unless you watch me weld, nobody has a sense of how much work it really is. I take a sheet of steel, I heat it, I hammer it, I heat it and hammer it some more, I add a little weld on, I grind it out, I add a little more weld on. Sometimes I’ll take the TIG welder and flow it out until it melts the way I want it. It takes hours to make a couple of feathers, a couple of talons.”

The feathers and talons refer to the artist’s latest accomplishment, a magnificent, realistic sculpture of an osprey that was completed over eight months beginning in August of last year and is now on display at the Granary Gallery in West Tisbury. Barney says he undertook the osprey because he’d just completed a realistic owl sculpture on commission, and had enjoyed the project greatly.

Between sessions of welding work on the osprey, Barney kept it on a roost – high on a steel pole in his back yard. The bird grew heavier as its creation progressed, and he recalls being almost unable to get it onto its stand as it neared completion. “I was staggering up the ladder with it,” he says – “my back hurt, and I was out of it for the next two days.”

As much as he loves welding and glass work, Barney Zeitz says there’s one medium that he loves most, and intends to keep working in after he can’t lift the heavy glass and steel anymore. “To me,” he says, “drawing is the most important thing of all. Even when I’m working in glass and metal, you can’t do anything unless you can draw it first.”

Back in the days when Barney was, as he says, pushing the lines of his art glass around, the woman he was living with told him he would never be a serious artist unless he learned to draw. His first response was to be deeply sad; his second was to enroll in classes at the Art Students League. He spent a month in New York City, and went back for more courses two years later.

Back from his classes – this was the early 1980s – Barney and some friends started a figure drawing group that met to draw every week for almost ten years. “What I learned is that to draw is really to see. Ann Margetson would yell at me, ‘Loosen up! Dirty the page!’ Because I was being so careful at first. Thank God for her; she was pesky but wonderful. It got so I’d come out of there looking like a coal miner.”

With his drawing skills, with his quirky, self-taught mastery of glass and a growing competence in metalwork, Barney Zeitz got his first major public commission – a sculpture for the Holocaust Memorial in Providence, R.I. – in 1993. Other projects followed: the Immigrant Memorial at Brewster Gardens in Plymouth, near Plymouth Rock; a commemorative sculpture for the Berkshire South Regional Community Center, and the Vietnam Era Memorial which now stands in the courtyard at Martha’s Vineyard Community Services in Oak Bluffs.

His largest and most ambitious piece is in his first medium, glass – a 35-panel window filling a wall at the Kew Gardens in Queens, N.Y. For this project, which consumed him for more than a year, Barney built a new workshop behind his home, with a replica of the 15-by-17-foot window on one wall.

“When I’m working on a big project that has some meaning to it,” Barney admits, “my life is crazy, and I’m probably not that great to live with.” His wife, Phyllis Vecchia, daughter Kaela and son Elliott get short shrift, he says, as a commission deadline nears.

At 61, Barney Zeitz knows what he can do, and he’s proud of what he has accomplished. But there remains a boyish energy about him – both the enthusiasms and the uncertainty of the 21-year-old. “I’m still trying to figure it out,” he says – “how to make a living at this.”

He still remembers the sting he felt taking one of his first stained-glass windows to the All-Island Art Show at the Tabernacle in Oak Bluffs, where a juror said dismissively of his work, “That’s not art, it’s craft.” But his lifetime attitude of problem-solving, of working his way through setbacks, has served him well.

“I’m trying to do things that are meaningful to people,” Barney Zeitz says. “Even though it may be a craft, I hope my work has an effect on people. Working with a material like stainless steel and transforming it into something like the osprey, it’s always like a miracle to me that I can do it.

“Now I can look back through my portfolio, and I think, ‘Wow, I can’t believe I made all this stuff.” While I was making all those things, I was feeling so insecure – it’s not going to be good enough, it’s not going to be done on time. At the end, I look at it and say, ‘Oh, that’s great.’ But it’s like a surprise to me every time.”

For more information about Barney Zeitz’s work click on: www.bzeitz.com

so far, for 40 years.

Growing up in Fall River, where his father worked selling corrugated boxes and packaging, the Island was a familiar weekend haunt for Barney. He recalls hanging out with a friend who had a place in Oak Bluffs, loving the diversity of the integrated summer community.

Barney hadn’t studied art in college – he was enrolled in an experimental program at the Amherst campus, with smaller classes and its own curriculum. “We read existential novels, and we had a whole course on revolution,” he recalls. That class must have been inspiring, because he became involved in the student antiwar activism of the day, at one point shutting down the campus.

Thinking back on those college years, Barney says: “I was pretty stressed out – it wasn’t an easy time for me. I mean, I was just a kid.”

Onthe Vineyard that spring 40 years ago, Barney recalls, “I picked up a book on how to do stained glass at a crafts store, and I bought $50 worth of stuff and made my first little lamp.” It was a kerosene lamp with a stained-glass shade; he set it on David Crohan’s piano at the Rare Duck Lounge on Circuit Avenue, and in one of those messages from the universe that shapes the course of a lifetime, the lamp sold the first night. What’s more, another couple at the table with the buyers commissioned Barney to make a stained-glass chandelier for them.

His career was launched. “I thought, I’m just going to keep going with this until I can’t do it anymore.”

Barney lived for two years in the back of the old Arts Collaborative building on Union Street in Vineyard Haven, just up from the ferry landing. “I had a little workbench in the front, and I made mirrors and boxes.” It was during these years that he learned to make his art windows, stained glass pieces whose leading served as the lines in the art. He refers to that process now as “pushing the lines around.”

When the Arts Collaborative closed, Barney rented a place from Mollie Kahn, whose Vineyard Arts shop was located in what is now the arts district of Oak Bluffs. As he recalls it, this was a time of intense learning and experimentation. It was also the time when he learned to weld, becoming the worker in metal and glass that he is today.

“I lived there for 12 years,” Barney says, “and I made windows that were so tall they wouldn’t even stand up in the room. I eventually outgrew the space, but my landlady, Mollie Kahn, was just a fabulous person. She loved what I was trying to do, this quest to make art that had some meaning to it. She was all about that.”

Mrs. Kahn had made money in the pottery supply business with her husband, who had died a few years earlier. Her place was filled with pottery materials, welding equipment and a kiln, a perfect laboratory for the young artist. “A lot of the chemicals I work with now,” Barney says, “were meant to be glazes for pottery. I’d take them and comb them onto glass, and I’d use Mollie’s kiln, doing these experiments. That was such a great opportunity – it was almost like being in art school, except I had to teach myself.”

Growing up as a self-taught artist, without a mentor, is an experience that cuts both ways, Barney reflects now. “I was an outsider right from day one,” he says with a wry grin. “I’m such an outsider, I don’t even get invited to the outsider art shows.”

But without a teacher to tell him what’s impossible, Barney was free to succeed by failing repeatedly, with enthusiasm. “I find that not having a teacher, I never copied my teacher’s style. I ended up doing things my way.”

Geology, the science of rocks, has been described as the study of heat, pressure and time. These same three ingredients inform the art of Barney Zeitz so fully that each completed work feels at once both effortless and the product of an intensely physical creative process. None of his work is conventionally pretty: Instead there’s an elemental beauty that celebrates both the recalcitrance of glass and steel, and the hard labor of the artist who burns and smelts and cuts and pounds them to his will.

Barney cheerfully describes the work of creating his art as “dirty, nasty, smelly, disgusting.” He’s a regular at the Vineyard Haven office of optometrist George Santos, having fragments of metal dug out of his eyes. He wears goggles, but sometimes the effort of his work dislodges the respirator just enough so a sliver of steel can ricochet in.

“The welding,” says Barney, “is very physically challenging, but I still like doing it. I don’t know how much longer I’ll be doing it, but I’ll definitely keep welding until I can’t do it anymore.”

Barney began welding during his years renting from Mollie Kahn, at first because he wanted to build his own frames. “I learned at the regional high school: adult ed, six Monday nights with a guy named John Holmes, in 1979.”

Now, he says, “Nobody else welds stainless steel the way I do. Unless you watch me weld, nobody has a sense of how much work it really is. I take a sheet of steel, I heat it, I hammer it, I heat it and hammer it some more, I add a little weld on, I grind it out, I add a little more weld on. Sometimes I’ll take the TIG welder and flow it out until it melts the way I want it. It takes hours to make a couple of feathers, a couple of talons.”

The feathers and talons refer to the artist’s latest accomplishment, a magnificent, realistic sculpture of an osprey that was completed over eight months beginning in August of last year and is now on display at the Granary Gallery in West Tisbury. Barney says he undertook the osprey because he’d just completed a realistic owl sculpture on commission, and had enjoyed the project greatly.

Between sessions of welding work on the osprey, Barney kept it on a roost – high on a steel pole in his back yard. The bird grew heavier as its creation progressed, and he recalls being almost unable to get it onto its stand as it neared completion. “I was staggering up the ladder with it,” he says – “my back hurt, and I was out of it for the next two days.”

As much as he loves welding and glass work, Barney Zeitz says there’s one medium that he loves most, and intends to keep working in after he can’t lift the heavy glass and steel anymore. “To me,” he says, “drawing is the most important thing of all. Even when I’m working in glass and metal, you can’t do anything unless you can draw it first.”

Back in the days when Barney was, as he says, pushing the lines of his art glass around, the woman he was living with told him he would never be a serious artist unless he learned to draw. His first response was to be deeply sad; his second was to enroll in classes at the Art Students League. He spent a month in New York City, and went back for more courses two years later.

Back from his classes – this was the early 1980s – Barney and some friends started a figure drawing group that met to draw every week for almost ten years. “What I learned is that to draw is really to see. Ann Margetson would yell at me, ‘Loosen up! Dirty the page!’ Because I was being so careful at first. Thank God for her; she was pesky but wonderful. It got so I’d come out of there looking like a coal miner.”

With his drawing skills, with his quirky, self-taught mastery of glass and a growing competence in metalwork, Barney Zeitz got his first major public commission – a sculpture for the Holocaust Memorial in Providence, R.I. – in 1993. Other projects followed: the Immigrant Memorial at Brewster Gardens in Plymouth, near Plymouth Rock; a commemorative sculpture for the Berkshire South Regional Community Center, and the Vietnam Era Memorial which now stands in the courtyard at Martha’s Vineyard Community Services in Oak Bluffs.

His largest and most ambitious piece is in his first medium, glass – a 35-panel window filling a wall at the Kew Gardens in Queens, N.Y. For this project, which consumed him for more than a year, Barney built a new workshop behind his home, with a replica of the 15-by-17-foot window on one wall.

“When I’m working on a big project that has some meaning to it,” Barney admits, “my life is crazy, and I’m probably not that great to live with.” His wife, Phyllis Vecchia, daughter Kaela and son Elliott get short shrift, he says, as a commission deadline nears.

At 61, Barney Zeitz knows what he can do, and he’s proud of what he has accomplished. But there remains a boyish energy about him – both the enthusiasms and the uncertainty of the 21-year-old. “I’m still trying to figure it out,” he says – “how to make a living at this.”

He still remembers the sting he felt taking one of his first stained-glass windows to the All-Island Art Show at the Tabernacle in Oak Bluffs, where a juror said dismissively of his work, “That’s not art, it’s craft.” But his lifetime attitude of problem-solving, of working his way through setbacks, has served him well.

“I’m trying to do things that are meaningful to people,” Barney Zeitz says. “Even though it may be a craft, I hope my work has an effect on people. Working with a material like stainless steel and transforming it into something like the osprey, it’s always like a miracle to me that I can do it.

“Now I can look back through my portfolio, and I think, ‘Wow, I can’t believe I made all this stuff.” While I was making all those things, I was feeling so insecure – it’s not going to be good enough, it’s not going to be done on time. At the end, I look at it and say, ‘Oh, that’s great.’ But it’s like a surprise to me every time.”

For more information about Barney Zeitz’s work click on: www.bzeitz.com