ARTIST PROFILE

En Plein Air - Marjorie Mason Reinventing Nature on Canvas

Profile by Moira C. Silva

All that we can experience is expanding right now. Making art is no different. Expanding. That’s an important word,” artist Marjorie Mason explains in an excited breath.

Every day, she’s expanding her understanding of art and beauty, and how she translates that onto canvas. Tomorrow, her perception of beauty will be transformed as she watches the sunrise at Lucy Vincent Beach or sunset in Menemsha. In the summer, Marjorie consciously tries to absorb the Island’s majestic moments, ideas as large as a thunderhead reflected in water or as small as a rose petal. Just noticing the majesty of color, like the way the light hits the top of a Philbin Beach dune at sunset can be a profound and visceral experience for her.

Marjorie began painting monotypes back in 1981, and has since worked in oil, plein air painting and abstracts. Her Tea Lane studio in Chilmark is nicely suited to her needs. The former garage has high ceilings and windows on all sides, offering plenty of light and an ever-changing view of the meadow situated just outside a window. In one corner, books featuring both well-known and obscure artists provide inspiration; glass jars of paint line the walls and a solitary large easel sits poised to capture the best north light. On raised tables, several unfinished paintings of all sizes and subjects await her joyful touch. Although on this particular afternoon, she seems to have enough energy to run an art marathon, she does at times pause and sip her chilled homemade lemonade, as she sits before her easel, contemplating her vision and its translation onto canvas.

Years ago, a teacher gave a demonstration that ignited Marjorie’s interest in montotypes. After completing an oil painting on a plexiglass plate, the teacher covered it with a piece of paper and squeezed the sheet of paper through the rollers of a printing press. When the paper passed through the press and was removed, the image was transferred from the glass onto the paper. There, before Marjorie’s eyes stood a piece of distinctive and finished art in one day.

Working in monotypes has served Marjorie’s artistic needs for more than 20 years. When she began, she admits she wasn’t ready for canvas and enjoyed the fast, gestural process of monotype. “It is spontaneous and satisfying. One is working with wet paint at all times and can easily change the image by adding or subtracting paint. It’s very playful, and I am now bringing that same easy sensibility to my work on canvas” she says.

In a monotype, the paint needs to stay wet, so there is no time for editing or mulling over the design or your approach to it. There is also no opportunity to layer paint, which is an advantage to canvas painting. Creating monotypes requires Marjorie to start in the morning and intensively attend to the piece all day, which means she does not have the chance to return with a refreshed perspective the next day. Although laborious and sometimes lonely, the process is largely wondrous and fulfilling and her viewers adore the finished product. Today, Marjorie continues to pursue her passion with monotypes, while she expands and explores which imagery best defines her artful life.

Marjorie’s eyes shine as she speaks confidently about her art, “You must pursue what you love so it can be shared. When you do, you make the world a better place. It’s not selfish to pursue your bliss.”

With this joyous confidence, Marjorie expanded on the success she had with monotypes to explore plein air, or “in the open air,” meaning painting on-site. She had a rare and magnificent opportunity to further her education by studying the plein air method with Don Stone, a much celebrated artist who works and teaches on Maine’s Monhegan Island. More recently, she benefited from painting excursions with John Ebersberger, a protégé of world-renowned painter, colorist and teacher Henry Hensche. This particular way of seeing color as it occurs naturally was literally eye-opening in the best possible way. As she puts it, “ the more we learn to truly see, the more aware we become. It is consciousness expanding to try to paint the vast abundance that is nature. One can argue that great art not only allows us to feel, but it acquaints us with our brilliance.”

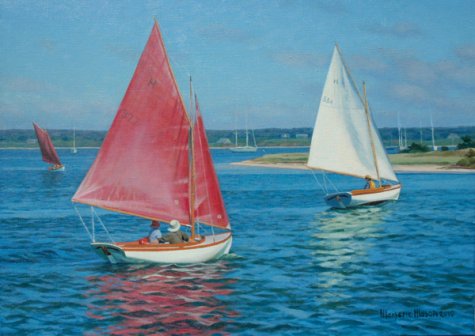

The demanding time constraints of plein air painting force the artist into some very creative problem solving. Marjorie notes that, “the light changes every minute, and can be especially dramatic early or later in the day. Painting outside means chasing the light which always seems to be moving faster than me.” Hues and shadows are constantly shifting, so she is forced to mix colors on the palette and the canvas. As in monotype the whole painting is done wet-on-wet and creates happy accidents. Finding the right white for a sail can be challenging, especially if the sail is reflecting the sun, the sky, the water or even the light off a nearby beach, all of which may not be see-able through the lens of a camera. “The more exotic the details, the more I can share by enhancing the painting with it,” she explains.

Things change so quickly that she cannot capture it all, but is content to grasp the gestural essence of what is seen and felt. This way she not only stays true to the moment, but builds a visual vocabulary of shadow and light colors that cannot be reproduced with a camera. “The sublime beauty of an evening sky won’t come out with the best camera. Painting it on location is not only the best chance to get accurate color, it is also an exhilarating experience,” she says with a smile.

Marjorie began developing linear abstracts for the corporate market and for her own enjoyment 15 years ago. Today they can be seen at Pik-Nik Gallery in Oak Bluffs. This non-representational work evolved from her landscape painting and is influenced by the work of the abstract expressionist artists Richard Diebenkorn and Mark Rothko. “Artists paint because we want to unravel this mystery we call beauty. Expanding our minds this way is joyful,” she says. While Marjorie continues to create montoypes, abstracts and plein air painting, she persists on her journey to find ever more sophisticated ways of visually sharing her ideas of beauty. She now understands her materials better. For example, working on linen requires different brushes from working in monotype. No matter which mode she is working in, the joy and suffering of making the paint conform are the same. “Some days it all flows from the brush like magic . . . it is that experience that I so much want to share with the world. I think somehow it will improve life for all of us,” she says.

Island sunsets are on Marjorie’s mind now as she explores landscape abstracts on a giant canvas. Her photographs of this summer’s sunsets and sunrises will inspire her as she paints through the winter. She will not try to paint a photograph, but instead, she will use the dramatic colors and subtle blendings, contrasts and shapes for ideas. Observing so many sunsets and sunrises expands her repertoire for sharing her vision of beauty. “It increases my understanding of what is compelling,” Marjorie adds. In her new sophisticated landscape abstracts one can almost feel the sun’s reflection, take in the expansive horizon or sense the rhythm of the waves.

“I am still learning to be the painter I was born to be. When I am painting, I’m living how I was meant to live. I think by the time I am 70, I will have it down,” Marjorie smiles.

Marjorie is excited about her annual end of summer show at the Christina Gallery. Her art finds life in those who observe and respond to it. When a gallery visitor weeps unabashedly in front of one of her paintings, that's her highest compliment. Marjorie, herself, has wept in front of the world’s greatest art in international museums. She adds, “I weep because I know how the artist felt; and in one glorious gesture they gave the world that perfect moment. They just got it right. When a viewer has an experience like that with my art, I feel united with that person.”

Staring away from the unfinished painting resting on the solitary easel, living her mantra of expansion – letting herself pause to take in the beauty of the meadow before attempting to formulate an expression, she pauses. “Genius elevates the consciousness of the viewer. We all want our consciousness to be raised. If one of my paintings makes someone breathe differently for a minute or transports them from everyday stress and routine, I am so happy,” she explains.

Her gaze then returns to her canvas with her brush in hand, emulating her philosophy that, “Sometimes, the only way to say something is through

a painting.”

The empty lemonade glasses signal that it’s time to depart from Marjorie’s studio, a place where infinite possibilities abound in art, thought and conversation. Upon leaving her studio in the woods, she first points to the nearby gardens and chickens she tends to and then to the landscaping she has done, which includes turning some large, mossy gray stones from her property into steps on a path. That is exactly what’s she has been talking about, reinventing what is around us in nature and allowing her to take us somewhere, turning stones into steps.

Every day, she’s expanding her understanding of art and beauty, and how she translates that onto canvas. Tomorrow, her perception of beauty will be transformed as she watches the sunrise at Lucy Vincent Beach or sunset in Menemsha. In the summer, Marjorie consciously tries to absorb the Island’s majestic moments, ideas as large as a thunderhead reflected in water or as small as a rose petal. Just noticing the majesty of color, like the way the light hits the top of a Philbin Beach dune at sunset can be a profound and visceral experience for her.

Marjorie began painting monotypes back in 1981, and has since worked in oil, plein air painting and abstracts. Her Tea Lane studio in Chilmark is nicely suited to her needs. The former garage has high ceilings and windows on all sides, offering plenty of light and an ever-changing view of the meadow situated just outside a window. In one corner, books featuring both well-known and obscure artists provide inspiration; glass jars of paint line the walls and a solitary large easel sits poised to capture the best north light. On raised tables, several unfinished paintings of all sizes and subjects await her joyful touch. Although on this particular afternoon, she seems to have enough energy to run an art marathon, she does at times pause and sip her chilled homemade lemonade, as she sits before her easel, contemplating her vision and its translation onto canvas.

Years ago, a teacher gave a demonstration that ignited Marjorie’s interest in montotypes. After completing an oil painting on a plexiglass plate, the teacher covered it with a piece of paper and squeezed the sheet of paper through the rollers of a printing press. When the paper passed through the press and was removed, the image was transferred from the glass onto the paper. There, before Marjorie’s eyes stood a piece of distinctive and finished art in one day.

Working in monotypes has served Marjorie’s artistic needs for more than 20 years. When she began, she admits she wasn’t ready for canvas and enjoyed the fast, gestural process of monotype. “It is spontaneous and satisfying. One is working with wet paint at all times and can easily change the image by adding or subtracting paint. It’s very playful, and I am now bringing that same easy sensibility to my work on canvas” she says.

In a monotype, the paint needs to stay wet, so there is no time for editing or mulling over the design or your approach to it. There is also no opportunity to layer paint, which is an advantage to canvas painting. Creating monotypes requires Marjorie to start in the morning and intensively attend to the piece all day, which means she does not have the chance to return with a refreshed perspective the next day. Although laborious and sometimes lonely, the process is largely wondrous and fulfilling and her viewers adore the finished product. Today, Marjorie continues to pursue her passion with monotypes, while she expands and explores which imagery best defines her artful life.

Marjorie’s eyes shine as she speaks confidently about her art, “You must pursue what you love so it can be shared. When you do, you make the world a better place. It’s not selfish to pursue your bliss.”

With this joyous confidence, Marjorie expanded on the success she had with monotypes to explore plein air, or “in the open air,” meaning painting on-site. She had a rare and magnificent opportunity to further her education by studying the plein air method with Don Stone, a much celebrated artist who works and teaches on Maine’s Monhegan Island. More recently, she benefited from painting excursions with John Ebersberger, a protégé of world-renowned painter, colorist and teacher Henry Hensche. This particular way of seeing color as it occurs naturally was literally eye-opening in the best possible way. As she puts it, “ the more we learn to truly see, the more aware we become. It is consciousness expanding to try to paint the vast abundance that is nature. One can argue that great art not only allows us to feel, but it acquaints us with our brilliance.”

The demanding time constraints of plein air painting force the artist into some very creative problem solving. Marjorie notes that, “the light changes every minute, and can be especially dramatic early or later in the day. Painting outside means chasing the light which always seems to be moving faster than me.” Hues and shadows are constantly shifting, so she is forced to mix colors on the palette and the canvas. As in monotype the whole painting is done wet-on-wet and creates happy accidents. Finding the right white for a sail can be challenging, especially if the sail is reflecting the sun, the sky, the water or even the light off a nearby beach, all of which may not be see-able through the lens of a camera. “The more exotic the details, the more I can share by enhancing the painting with it,” she explains.

Things change so quickly that she cannot capture it all, but is content to grasp the gestural essence of what is seen and felt. This way she not only stays true to the moment, but builds a visual vocabulary of shadow and light colors that cannot be reproduced with a camera. “The sublime beauty of an evening sky won’t come out with the best camera. Painting it on location is not only the best chance to get accurate color, it is also an exhilarating experience,” she says with a smile.

Marjorie began developing linear abstracts for the corporate market and for her own enjoyment 15 years ago. Today they can be seen at Pik-Nik Gallery in Oak Bluffs. This non-representational work evolved from her landscape painting and is influenced by the work of the abstract expressionist artists Richard Diebenkorn and Mark Rothko. “Artists paint because we want to unravel this mystery we call beauty. Expanding our minds this way is joyful,” she says. While Marjorie continues to create montoypes, abstracts and plein air painting, she persists on her journey to find ever more sophisticated ways of visually sharing her ideas of beauty. She now understands her materials better. For example, working on linen requires different brushes from working in monotype. No matter which mode she is working in, the joy and suffering of making the paint conform are the same. “Some days it all flows from the brush like magic . . . it is that experience that I so much want to share with the world. I think somehow it will improve life for all of us,” she says.

Island sunsets are on Marjorie’s mind now as she explores landscape abstracts on a giant canvas. Her photographs of this summer’s sunsets and sunrises will inspire her as she paints through the winter. She will not try to paint a photograph, but instead, she will use the dramatic colors and subtle blendings, contrasts and shapes for ideas. Observing so many sunsets and sunrises expands her repertoire for sharing her vision of beauty. “It increases my understanding of what is compelling,” Marjorie adds. In her new sophisticated landscape abstracts one can almost feel the sun’s reflection, take in the expansive horizon or sense the rhythm of the waves.

“I am still learning to be the painter I was born to be. When I am painting, I’m living how I was meant to live. I think by the time I am 70, I will have it down,” Marjorie smiles.

Marjorie is excited about her annual end of summer show at the Christina Gallery. Her art finds life in those who observe and respond to it. When a gallery visitor weeps unabashedly in front of one of her paintings, that's her highest compliment. Marjorie, herself, has wept in front of the world’s greatest art in international museums. She adds, “I weep because I know how the artist felt; and in one glorious gesture they gave the world that perfect moment. They just got it right. When a viewer has an experience like that with my art, I feel united with that person.”

Staring away from the unfinished painting resting on the solitary easel, living her mantra of expansion – letting herself pause to take in the beauty of the meadow before attempting to formulate an expression, she pauses. “Genius elevates the consciousness of the viewer. We all want our consciousness to be raised. If one of my paintings makes someone breathe differently for a minute or transports them from everyday stress and routine, I am so happy,” she explains.

Her gaze then returns to her canvas with her brush in hand, emulating her philosophy that, “Sometimes, the only way to say something is through

a painting.”

The empty lemonade glasses signal that it’s time to depart from Marjorie’s studio, a place where infinite possibilities abound in art, thought and conversation. Upon leaving her studio in the woods, she first points to the nearby gardens and chickens she tends to and then to the landscaping she has done, which includes turning some large, mossy gray stones from her property into steps on a path. That is exactly what’s she has been talking about, reinventing what is around us in nature and allowing her to take us somewhere, turning stones into steps.